CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

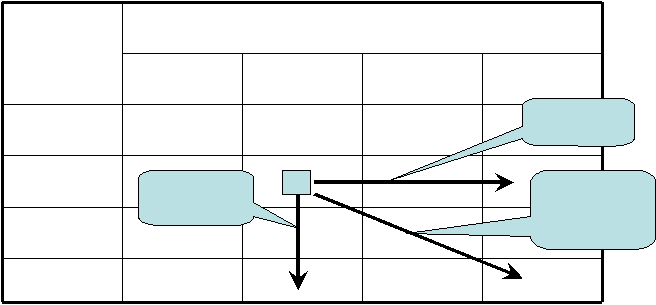

2.1. Diversification Strategy

Product/Service

Alternatives

Market Alternatives

Reduced

Product/Services

Reduce Market

Existing Market

Expanded

Market

New Market

Market

diversification

Existing

Product/Services

Modified

Product/Services

Product

diversification

Market and

Product

diversification

New

Product/Services

Figure 1: Competitive Position Growth Alternatives ( Woodcock & Beamish, 13: 2003 )

Diversification is a part of corporate-strategy (Hill & Jones: 2001; Pearce II & Robinson:

2003; Hit et al: 2007). Diversification inside corporate strategy level means this option

may bring the future direction of the company.

2.2. Reasons for diversification

Every strategy always has

reasons

because strategy

would

be

used

by

the

company

to

fulfill its goals. Reasoning is a basic-concept for effective-strategy. Hit et al (173: 2007)

explained some reasons why a company uses diversification-strategy

|

|

2.2.1. Value Creating Diversification

•

Economies of scope (related diversification)

o

Sharing activities

o

Transferring core competencies

•

Market Power (related diversification)

o

Blocking competitors through multipoint competition

o

Vertical integration

•

Financial economies (unrelated diversification)

o

Efficient internal capital allocation

o

Business restructuring

2.2.2. Value Neutral Diversification

•

Antitrust regulation

•

Tax laws

•

Low performance

•

Uncertain future cash flows

•

Risk reduction for firm

•

Tangible resources

•

Intangible resources

2.2.3. Value Reducing Diversification

•

Diversifying managerial employment risk

•

Increasing managerial compensation

|

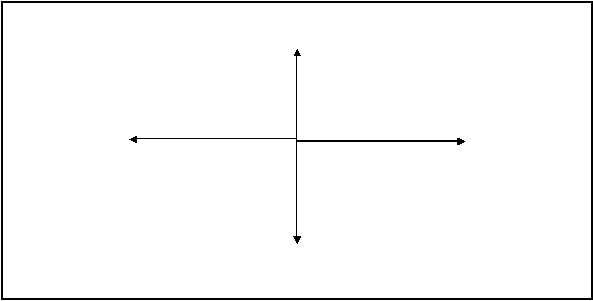

Related

Constrained

diversification

Both operational

Corporate

relatedness

Unrelated

diversification

Related linked

diversification

Operational relatedness:

Sharing

Activities

Between

Business

High

Low

Low

High

Corporate relatedness:

transforming core competencies into business

Figure 2: Value Creating Diversification Strategies: Operational and Corporate

Relatedness

2.3. Operational and Corporate Relatedness

When

a

company

decided

to

do diversification,

it

was

important

to

pay

attention

in

relation between core-competencies and operational

of

the

company.

Operational

relatedness and corporate relatedness are the ways to diversify for creating value for the

company. Study about relation of these two things showed how important resources and

key-competencies are when company needed to diversify.

2.4. Levels of Diversification (Hill et al, 170: 2007)

•

Single Business: 95% or more of revenue comes from a single business.

•

Dominant

Business: between 70%

and

95%

of

revenue

comes

from

a

single

business

•

Moderate to High Level of Diversification

|

|

o

Related Constrained:

less than 70% of revenue comes

from the dominant

business, and all business share product, technological, and distribution

linkages.

o

Related linked (mixed related and unrelated):

less than 70% of revenue

comes from the dominant business and there are only limited links

between businesses.

•

Very High Levels of Diversification

o

Unrelated:

less than 70% of revenue comes

from the dominant business

and there are no common links between businesses.

2.5. Types of Diversification

•

Related Diversification

Diversification

into a

new

business activity

is

linked

to

a

company’s existing

business activity or activities, by commonality between one or more components

of each activity’s value chain. Normally, these linkages are based on

manufacturing,

marketing

or technological commonalities.

Example:

Philip

Morris did diversification

by acquiring Miller Brewing because there is closed

relation between beer and smokers.

•

Unrelated Diversification

Diversification into a new business area has no obvious connecting with any of

the company’s existing areas.

|

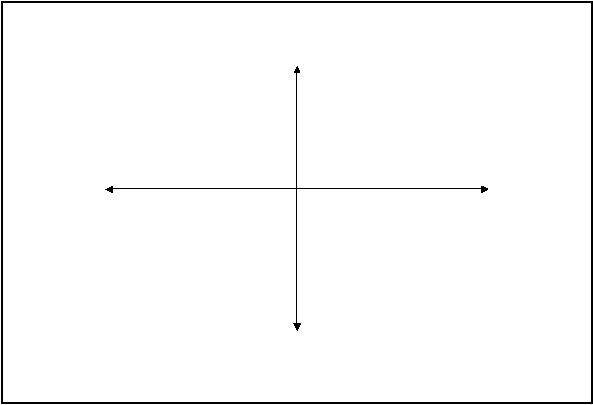

2.6. Diversification for Grand Strategy

As

explained

before,

diversification

may

become

a

variant

of corporate-strategy.

Diversification together with other variant of strategies

might be

used by a company to

reach

its goals.

There are two

matrixes

which connected with diversification. First, was

Grand Strategy Selection Matrix and second was Model of Grand Strategy Clusters. In

Grand Strategy Matrix we can see that diversification would be chosen by the company

with strong external pressure/inducements. In Strategy Cluster Matrix, diversification

would be used in slow market-growth. The target of this strategy was to create new-value

for the company outside the existing market at this moment.

Overcome Weakness

Internal

(redirected

resources

Turnaround or

retrenchment Divesture

Liquidation

I

II

IV

Vertical Integration

Conglomerate

diversification

External

(acquisition

or

merger

for

within the firm)

Concentrated growth

Market development

Product development

Innovation

III

Horizontal Integration

Concentric diversification

Joint venture

resource

capability)

Maximize Strengths

Figure 3: Grand Strategy Selection Matrix (Pierce II & Robinson Jr, 208: 2003)

|

Rapid Market Growth

Strong

Competitive

•

Concentrated Growth

•

Vertical Integration

•

Concentric

diversification

I

II

•

Reformulation

of

concentrated growth

•

Horizontal integration

•

Divestiture

•

Liquidation

Weak

Competitive

Forces

IV

•

Concentric

diversification

•

Conglomerate

diversification

•

Joint ventures

III

•

Turnaround

or

retrenchment

•

Concentric

diversification

•

Conglomerate

diversification

•

Divestiture

•

Liquidation

Forces

Slow Market Growth

Figure 4: Model of Grand Strategy Clusters (Pearce II & Robinson Jr, 210: 2003)

2.7. Growth Strategy: Diversification

Definition

A strategy based on investing in companies and sectors which are growing faster than

their peers.

WIKA has already decided to grow as named the roadmap to 2010. In the end of the

roadmap, the company hopes to be the excellent company in Southeast Asia with Sales

Growth of 36%. Core business

is still

in construction but

it

focuses

in EPC, Investment

and

International

Construction.

From 2002

to

2010

WIKA

has

gradually

changed

its

business-lines but never leave the construction as a core business.

|

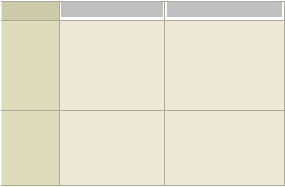

Existing Products

New Products

Existing

Markets

Market

Penetration

Product Development

New

Markets

Market

Diversification

2.7.1. Ansoff Matrix

Igor Ansoff presented a matrix that focused on the firm's present and potential products

and markets (customers). By considering ways to grow via existing products and new

products,

and

in

existing

markets

and

new

markets,

there

are

four

possible

product-

market combinations. Ansoff's matrix is shown below:

Development

Figure 5: Anzoff Matrix

2.7.2. What is the product – Market-Grid - Description

The Product/ Market Grid of Ansoff is a model that has proven to be very useful in

business unit strategy processes to determine business growth opportunities.The Product/

Market Grid has two dimensions: products and

markets.Over

these

2

dimensions,

four

growth strategies can be formed.

Four growth strategies in the product/market grid:

1. Market Penetration. Sell more of the same products or service in current

markets.

These

strategies

normally try to change

incidental

clients

to

regular

clients, and

regular client

into

heavy clients.

Typical

systems are

volume

|

|

discounts, bonus cards and Customer Relationship Management. Strategy is often

to achieve economies of scale through more efficient manufacturing, more

efficient distribution, more purchasing power, overhead sharing.

2. Market Development. Sell more of the same products or services in new

markets.

These

strategies

often

try to

lure

clients

away

from competitors

or

introduce existing products in foreign markets or introduce new brand names in a

market. New

markets can be geographic of functional, such as

when we sell the

same product for another purpose. Small modifications may be necessary. Beware

of cultural differences.

3. Product Development. Sell new products or services

in current markets.

These

strategies

often

try

to

sell

other

products to (regular) clients. These can be

accessories, add-ons, or completely new products. Cross-selling. Often, existing

communication channels are used.

4. Diversification. Sell new products or service in new markets. These strategies are

the

most

risky

type

of strategies.

Often

there

is

a

credibility

focus

in

the

communication to explain why the company

enters

new

markets with new

products. On the other hand diversification strategies also can decrease risk,

because a

large corporation can spread certain risks if

it operates on

more than

one market.

Diversification can be done in four ways:

-

Horizontal

diversification.

This

occurs

when

the

company

acquires

or

develops

new products

that could appeal to

its current customer

groups

|

|

even though those new products

may be technologically

unrelated

to the

existing product lines.(new products, current market)

-

Vertical diversification. The company moves into the business of its

suppliers or into the business of its customers. (move into firms supplier's

or customer's business)

-

Concentric

diversification. This results

in

new product lines or services

that have technological and/or marketing synergies with existing product

lines, even though the products may appeal to a new customer group. (new

product closely related to current product in new market)

-

Conglomerate diversification. This occurs

when there

is neither

technological nor marketing synergy and this requires reaching new

customer groups. Sometimes used by large companies seeking ways to

balance a cyclical portfolio with a non-cyclical one.(new product in new

market)

There are two types of diversification:

-

related

-

unrelated diversification.

Related diversification means that the firm remains in a particular industry, but diversify into another type of

product

to be sold

to

new markets.

Unrelated diversification refers to a situation where the firm completely ventures into a new business area to

serve

new markets with

its

new product development.

New capital

investments

are also needed.

In this

scenario, it would mean that the firm is entering into an industry that it has little experience with limited or no

knowledge of the industry.

|

|

2.7.3. Selecting a Product-Market Growth Strategy

The market penetration strategy is the least risky since it leverages many of the firm's

existing resources and capabilities. In a growing market, simply maintaining market share

will

result

in

growth,

and

there

may

exist opportunities

to

increase market

share

if

competitors reach capacity limits. However, market penetration has limits, and once the

market approaches saturation another strategy must be pursued if the firm is to continue

to grow.

Market

development

options

include

the

pursuit

of additional

market

segments

or

geographical regions. The development of new

markets

for the product may be a

good

strategy if the firm's core competencies are related more to the specific product than to its

experience

with a

specific

market segment.

Because

the

firm is

expanding

into a

new

market, a market development strategy typically has more risk than a market penetration

strategy.

A

product development strategy may be appropriate if the firm's strengths are related to

its

specific

customers

rather than to

the specific

product

itself.

In this

situation, it

can

leverage its strengths by developing a new product targeted to its existing customers.

Similar to the case of new market development, new product development carries more

risk than simply attempting to increase market share.

Diversification is

the

most

risky

of

the

four

growth

strategies

since

it

requires

both

product and market development and may be outside the core competencies of the firm.

In

fact, this quadrant of

the

matrix

has been referred

to by some as

the

"suicide cell".

|

|

However, diversification may be a reasonable choice if the high risk is compensated by

the

chance

of

a

high

rate

of return.

Other

advantages

of diversification

include

the

potential to gain a foothold in an attractive industry and the reduction of overall business

portfolio risk.

The

product/market

grid

of

Ansoff

is

a

model

that

has

proven

to

be

very

useful

in

business unit strategy processes to determine

business

growth

opportunities.

The

product/market grid has two dimensions: products and markets.

2.8. What kind of decision will be the best in diversification?

What is the basis?

2.8.1. Diversity to unrelated industry

Example: Conglomerate PT Astra International Tbk.

In 1957, Astra was established as a trading company. Over the course of its development,

Astra has formed a number of strategic alliances with leading global players in various

industries.

Since 1990, the Company had been a go public company, listed on both the Jakarta and

Surabaya Stock Exchanges, now known as the Indonesia Stock Exchange with the

Company’s

market capitalization

as

of

31

December 2007 stood

at

Rp

110.5

trillion.

Astra now has six

core businesses: Automotive, Financial Services, Heavy Equipment,

Agribusiness, Information Technology and Infrastructure. At year-end 2007, Astra Group

had a workforce of 116,867 people, spread across 130 subsidiaries and affiliates.

|

Table 1: Financial Performance

(Rpbn)

Net revenue

Operating profit

2006

2007

Growth (%)

2006

2007

Growth (%)

Automotive Financial

services Agribusiness

Information technology

Heavy equipment and mining

Others

Total

Less elimination

Total consolidated

Contribution (%)

30,259.0

38,318.4

26.6

7,567.8

7,310.5

(3.4)

3,758.0

5,961.0

58.6

619.0

725.6

17.2

13,719.6

18,165.6

32.4

28.9

28.3

(2.0)

55,952.2

70,509.3

26.0

(243.0)

(326.4)

34.3

55,709.2

70,183.0

26.0

859.1

1,717.9

99.9

727.0

1,355.6

86.5

1,198.6

2,907.1

142.5

76.7

95.1

23.9

1,340.1

2,393.3

78.6

(10.4)

(8.9)

(14.4)

4,191.2

8,460.0

101.9

52.0

41.5

(20.3)

4,243.2

8,501.5

100.4

Automotive Financial

services Agribusiness

Information technology

Heavy equipment and mining

Others

54.1

54.3

13.5

10.4

6.7

8.5

1.1

1.0

24.5

25.8

0.1

0.0

20.5

20.3

17.3

16.0

28.6

34.4

1.8

1.1

32.0

28.3

(0.2)

(0.1)

Total

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

Source: Bahana Securities

2.8.2. Diversity to related-industry

|

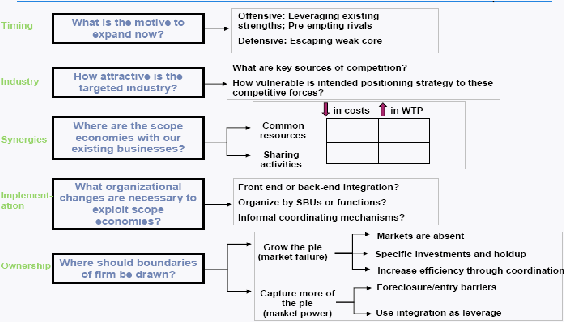

Figure 6: Strategies of Related Diversification

Timing: The first question to assess is the competitive strength of the firm that is looking

to expand. Is the motive to expand an offensive one-- triggered by healthy margins in the

core business, and strengths that can be leveraged elsewhere? Or, is it primarily

defensive,

where a

firm is

looking

to

“escape”

its declining

core?

Unfortunately, scope

expansions are in most cases not effective in solving the latter predicament; in addition,

they are

unlikely to

leverage

any existing strengths of the firm in

such a setting. Thus,

Bausch and Lomb, the market leader in soft contact lenses, decided to expand away from

its core business when growth slowed and competitors attacked with new technologies

such as cast

molding. The company

invested

in electric toothbrushes, dental aids, skin

ointments, and hearing aids. After several years, and having seen its market share in its

core business decline from 40% to 16% (while Johnson and Johnson introduced the idea

of

disposable

lenses),

Bausch and

Lomb exited

many

of

these

noncore

businesses

and

looked to focus on the core again. Companies in similar situations often do well not by

|

|

looking outward but

inward:

invariably, a more effective solution is to

identify ways to

solve the problems in, and “profit from the core”1, as companies like Harley-Davidson

have done.

Industry

attractiveness:

Structurally, how attractive is the new business arena being

considered

for

expansion? Do

incumbents

enjoy

healthy

margins

or

are

competition

likely to be fierce and profits meager? The familiar “five forces” analysis is useful not

only in predicting industry profitability but, more importantly, in identifying the various

sources of competition that

the

company

is

likely

to

face. Specifically,

it

is

useful

to

examine

whether and

how the

firm’s

intended entry strategy can effectively combat the

likely competitive forces. For example, consider the furniture industry. An entrant that

seeks to exploit scale economies by automating manufacturing processes

is likely to be

more vulnerable to the industry’s cyclical dynamics since automation would increase the

fraction of its costs that are fixed. On the other hand, the “infinite variety” in designs that

characterizes the industry also makes it difficult for manufacturers to develop brands with

consistent identities and carve out a high-end position.

Scope

economies

with

existing

business:

The

viability

of an

entry strategy

leaves

unanswered the question of which firm is in the best position to pull off such a strategy.

Specifically, what are the scope economies or

synergies

with

the firm’s

existing

businesses: might expansion into the new businesses either leverage particular strengths

from the existing ones, or benefit them in turn? Exhibit 1 illustrates the different sources

of such synergies. These might arise from cost-sharing: for example, the centralization of

procurement, combination of staff functions, economies

in distribution and logistics, or

common production platforms. Or, they might enhance revenues of the combined

|

|

businesses by mechanisms such as cross-selling, bundling, and one-stop shopping. While

cost synergies are often the driving force in scope expansions and mergers, the search for

revenue synergies has become more common as well. For example, several mergers

between high-end and low-end machine tool manufacturers in the last decade were driven

by the desire to combine breadth of product offerings in “one-stop shopping” for

industrial customers. Health care delivery has seen the emergence of multi-business firms

like

Covenant

Health

Systems,

whose outpatient

ambulatory

care

centers

have

led

to

more

referrals

for

more

profitable

inpatient

care.

And,

cross-selling

motivations have

resulted in financial services companies like Charles Schwab expanding to offer products

ranging from money market funds to investment advisory services.

Each of the synergies described above stems

from the sharing of activities by different

businesses. Activity

analysis is

a

useful,

and

concrete,

approach

to

evaluating

scope

economies. At the same

time, it

is useful to keep in mind that tangible activity

coordination

is

not

the

only

source

of

synergies.

Often,

synergies

can arise

from the

sharing of resources or intangible skills.

These

might include a common brand,

reputation, specific knowledge and expertise, managerial talent, systems and processes,

values, or even a common culture.

As these examples illustrate, resource sharing, while intangible, can be no less important.

More

importantly,

it suggests a different

way to evaluate the question of

“relatedness”

between any two businesses: rather than simply ask whether the products being sold by

the

businesses

are

related,

one

ought

to also

examine

whether

there

are

common

competencies

required to

succeed

in

these

businesses.

This

can often

lead

to

counterintuitive,

but

no

less

powerful, expansion

decisions. For

example,

Honda

|

|

expanded into cars, motorcycles, lawn mowers, and generators, leveraging its

competence in engines and power trains. Canon expanded into copiers, laser printers, and

cameras, exploiting its competencies in optics, imaging, and processor controls. And,

Minebea expanded from ball bearings to semiconductors, leveraging its competence in

miniaturized manufacturing.

Each of these examples suggests a useful principle

to

keep

in

mind when

evaluating

resource sharing benefits: these benefits are

most compelling when the competencies

in

question are not only

(i) important drivers of performance in that business, but they are also (ii) distinctive or

unique to the firm.

Organizational

mechanisms

for

coordination:

Having examined the potential sources

of synergies, one ought to scrutinize how exactly they will be realized. Specifically, what

organizational mechanisms need to be put in place to ensure this? Firms often deem this

question to fall under the domain of “implementation”. However, failing to think through

the organizational choices and changes that accompany any scope expansion is a

common reason why

mergers

fail.

Consider,

for example,

Saatchi and Saatchi’s

foray

into the consulting businesses in the 1980s. Regardless of whether one viewed the

potential synergies between advertising and consulting services to be large or small, the

firm’s approach to organizational integration proved to be the decisive factor in its failed

expansion. Specifically, its approach of “front-end separation, back-end integration”—

while successful in integrating its earlier advertising acquisitions—was flawed here, in

light of the differences between the “push based” budgeting systems

common in

consulting and the “pull based” approach intrinsic to advertising.

|

|

The

nature

of

organizational coordination

will

of

course

be

informed

by

the

types

of

synergies identified above. For example, the incentives to cross-sell two products will be

greater when there is a common sales-force for both products than with different ones for

each. Or, the ability to leverage company-wide competencies is often easier with a

functional organizational structure than with a divisional one. And, in addition to the role

of the formal organizational structure in facilitating (or impeding) coordination, informal

mechanisms can often be quite powerful in “boundary-spanning” as well: company-wide

norms, values, and cultures. Recognizing, and acting on, these organizational changes can

be critical to realizing the benefits of scope in practice.

Ownership:

Extracting

the rents from expansion

into a new arena does not require that

companies fully own the new business as well. The choice of ownership (i.e., where the

boundaries

of

the

firm

should

be drawn) is relevant for

most

horizontal

expansion

decisions, but is particularly central to firms’ decisions on whether to expand into

adjacent parts of the value chain—the vertical integration question. Therefore, although

the key insights behind the logic of ownership are quite general, they are discussed, in

what follows, largely in the context of the choice to vertically integrate.

Source: Adopted from Bharat N. Anand, Strategies of Related Diversification (2005)

Example: Engineering and Construction: PT Wijaya Karya (Persero) Tbk.

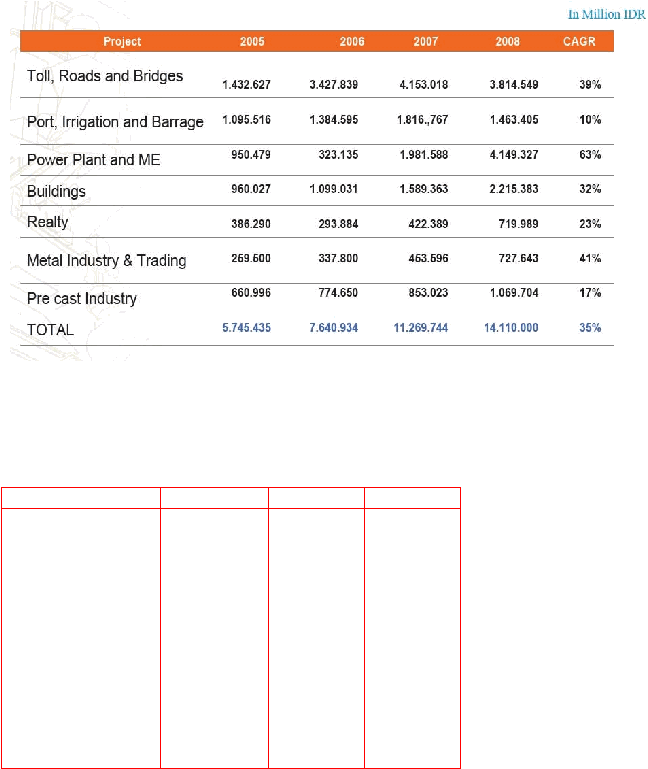

Table 2: Growth of order

|

Source: company

Table 3: Financial Performance

Year to 31 Dec

2006

2007

2008F

Revenue (IDRb)

EBITDA (IDRb)

Net Profit (IDRb)

EPS (IDR)

Growth (%)

P/E (x)

BVPS (IDR)

P/BV (x)221

EV/EBITDA (x)

ROA (%)

ROE (%)

Dividend (IDR)

Dividend Yield (%)

3.049

135

94

16

37.3

36.7

69

8.6

25.6

3.5

23.3

13

2.2

4.285

242

129

22

37.5

14.5

221

1.4

3.4

3.1

10.0

4.8

1.5

6.450

281

152

26

17.8

12.3

240

1.3

4.7

2.7

10.8

6.6

2.1

Source: company, Bahana Estimates

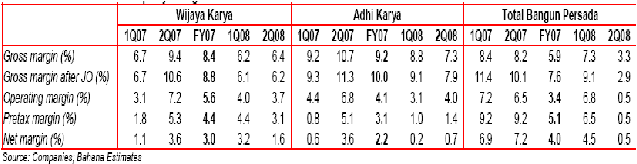

Table 4: Construction Company Margin

|

WIKA : fully diversified; ADHI : partly diversified; TOTL : focus

TOTL net margin was higher than the others when the construction growth was high in

2007. On the other hand when oil prices

increased significantly since the beginning of

2008, the cost of construction company raised and could possibly ruin its profit as shown

at above figure. As escalation clause on cost of construction only applicable for

multi

year projects and mostly for companies with exposures to government projects, the

benefited companies would be WIKA and ADHI.

WIKA would be the most benefited because of it diversified business model to reduce the

volatility

in margin

as

a

result of the

uncertain raw

material

cost and

global

finance-

turmoil.

2.8.3. Do not diversify

From the figure below, there are many other industries which have interesting growth in

its

own

business.

It

means

even focusing

in

one

line

of

business;

it

will

still

have

opportunity to grow in its industries.

|

Table 5: The growth of industry in Indonesia

Mkt Cap

US$mn

EPS Growth (%)

05A

06A

07A

08F

ROE (%)

05A

06A

07A

08F

Indonesia

Banking

Mining & Energy

Telecom

Consumer & Retail

Automotive

Cement**

Plantations

Heavy Equipments

Property

Oil & Gas services

Construction

Toll Road

Poultry

115,367

30,836

29,616

19,487

9,892

7,931

5,296

3,944

3,545

2,358

651

270

280

79

2.7

43.1

50.9

27.1

-19.5

68.4

23.0

21.9

16.2

52.0

107.6

33.8

15.9

26.5

26.1

19.0

-10.4

96.4

10.3

8.3

0.9

-32.0

58.7

27.7

44.7

-16.4

45.3

47.0

-6.1

36.8

112.2

55.3

-4.4

-10.9

59.5

31.8

-0.1

-8.1

3.6

11.0

N/A

N/A

3.1

57.6

7.1

35.6

19.8

55.4

22.8

50.3

-29.5

59.0

N/A

480.5

-14.7

-18.2

20.6

22.5

27.2

26.3

18.7

18.3

18.7

19.5

23.8

30.7

45.3

40.1

27.4

32.0

31.9

30.6

4.4

6.2

6.0

6.4

26.7

16.6

22.2

23.7

13.0

15.3

18.5

20.7

25.6

23.7

35.9

39.7

25.6

20.4

26.0

27.7

10.3

8.5

6.4

6.7

N/A

15.5

14.4

20.2

20.7

22.6

12.8

16.9

13.2

16.8

5.8

8.1

11.0

39.9

26.7

18.0

Source: Bahana Securities

|